Ralph Atkins (Financial Times)

The world is awash with more debt than before the global financial crisis erupted in 2007, with China’s debt relative to its economic size now exceeding US levels, according to a report.

Global debt has increased by $57tn since 2007 to almost $200tn — far outpacing economic growth, calculates McKinsey & Co, the consultancy. As a share of gross domestic product, debt has risen from 270 per cent to 286 per cent.

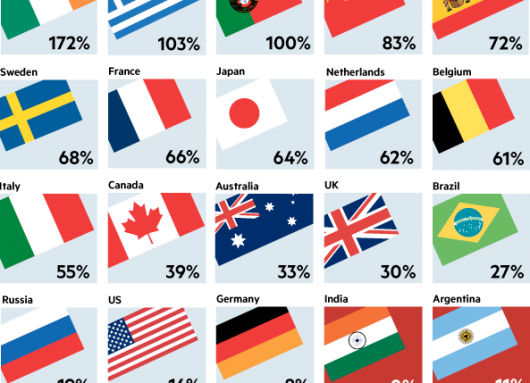

McKinsey’s survey of debt across 47 countries — illustrated in an FT interactive graphic — highlights how hopes that the turmoil of the past eight years would spur widespread “deleveraging” to safer levels of indebtedness were misplaced. The report calls for “fresh approaches” to preventing future debt crises.

“Overall debt relative to gross domestic product is now higher in most nations than it was before the crisis,” McKinsey reports. “Higher levels of debt pose questions about financial stability.”

Overall, almost half of the increase in global debt since 2007 was in developing economies, but a third was the result of higher government debt levels in advanced economies. Households have also increased debt levels across economies — the most notable exceptions being crisis-hit countries such as Ireland and the US.

“There are few indications that the current trajectory of rising leverage will change,” the report says. “This calls into question basic assumptions about debt and deleveraging and the adequacy of tools available to manage debt and avoid future crises.”

Countries that McKinsey warns face “potential vulnerabilities” because of high household debt include the Netherlands, South Korea, Canada, Sweden, Australia, Malalysia and Thailand. “It is like a balloon. If you squeeze debt in one place, it pops up somewhere else in the system,” says Richard Dobbs, one of the report’s authors.

One “bright spot,” McKinsey says, is evidence of deleveraging by banks. Financial sector debt relative to GDP has declined in the US and a few other crisis-hit countries, and stabilised in other advanced economies.

China’s total debt, including the financial sector, has nearly quadrupled since 2007 to the equivalent of 282 per cent of GDP. That was higher than in the US — although China is lower if financial sector debt is excluded to avoid double counting. McKinsey warns of risks in China’s property sector, local government financing and a rapidly expanding “shadow” banking system.

The country’s overall debt “appears manageable”, McKinsey says, but its indebtedness would restrict its ability to compensate for slower long-term growth in advanced economies.

“Before the [post-2007] crisis there was one area where debt was very low and stable, and that was China,” says Luigi Buttiglione, head of global strategy at hedge fund Brevan Howard and co-author of a report in September on global indebtedness. “When there was a crisis in the west, China could lever up. Now that is not the case.”

The report is likely to fuel debates among economists about what is an appropriate level of debt in an economy. McKinsey argues much of the expansion in developing countries has reflected the healthy development of financial markets, but in advanced economies high debt could constrain growth and create fresh financial vulnerabilities.

High debt levels could make it harder for central banks to “normalise” monetary policy without disrupting the real economy — the US Federal Reserve plans to raise interest rates this year for the first time since 2006. “High debt levels are an outward sign of structural problems,” says Charles Dumas, chairman of Lombard Street Research.

The report comes as Greece this week has pushed for a radical rethink by its creditors of ways of tackling its debt and economic problems. Among the “fresh approaches” McKinsey suggests are innovations in mortgages and other debt contracts to better share risks between borrowers and creditors. Other steps it discusses to prevent future crises include debt reschedulings and even writing off debt bought by central banks under “quantitative easing” programmes.

If debt held by government agencies and the central bank were excluded, Japan’s government debt to GDP ratio would fall from 234 per cent to 94 per cent. But such quick-fix “deleveraging” could itself cause financial turmoil, McKinsey acknowledges.

McKinsey’s conclusions echo warnings by the Bank for International Settlements in Basel, which acts as a think-tank for central bankers. BIS research had found that “when private sector credit-to-GDP ratios are significantly above their long-term trend, banking strains are likely to follow within three years”, Jaime Caruana, BIS general manager, said in a speech late last year.