Two writings published by judge Daniel Rafecas, which were found in the safebox of the deceased prosecutor’s office. In these writings, prosecutor Nisman requests the Executive Branch to appear before the Security Council of the UN and request the arrest of Iranians accused by the AMIA bombing. In texts dated December 2014 and January 2015, Nisman also praises the policies and support of the investigation by Nestor and Cristina Kirchner regarding the AMIA bombing in 1994, contradicting his own criminal complaint against President Cristina Kirchner.

TRANSLATION————————————————————————————-

Public Prosecutor’s Office of the Argentine Republic

It is hereby recorded that, on this day, Mr. Alberto Gentili, on account of being in charge of the Prosecutorial Investigation Unit in the AMIA case, requested me, the undersigned, to inform him of different matters inherent to the prosecution office. Among such matters, I informed him of the existence of a set of documents, which had been signed by Mr. Alberto Nisman. At least all five Secretaries who work in this Prosecutorial Unit —Sebastian Ferrante, Vanesa Alfaro, Fernando Comparato, Armando Antao Cortez, and Fernando Scorpaniti—, as well as the undersigned, were aware of the existence of such documents. Among the various aspects of the investigation in the AMIA case, for quite a long time work was focused on finding a legal recourse that would make it possible to secure the effective extradition of the Iranian indictees in order to bring them before the courts and proceed with their prosecution. Finally, a base brief was prepared, which contained a record of the lack of cooperation with the investigation that the Iranian authorities had shown throughout the years within the framework of the case. On the basis of these circumstances, the abovementioned base brief proposed a legal recourse to secure the surrender of the accused Iranian nationals to the Argentine courts. In this way, through the Argentine Attorney General’s Office —in keeping with section 21, subsection “d”, sections 23 and 30, and section 33, subsection “s” of law No. 24946—, Prosecutor Alberto Nisman intended to file a request with the Argentine Executive for it to require the Security Council of the United Nations, through the relevant channels, to implement the mandatory mechanisms established in Chapter VII of the Charter of the United Nations and require the Islamic Republic of Iran to arrest the eight (8) Iranian indictees (Ali Akbar Hashemi Bahramaie Rafsanjani, Ali Fallahijan, Ali Akbar Velayati, Mohsen Rezai, Ahmad Vahidi, Mohsen Rabbani, Ahmad Reza Asghari or Mohsen Randjbaran, and Hadi Soleimpanpour) for their extradition and subsequent prosecution for their liability in relation to the attack on the AMIA building on 18 July 1994. The national and international arrests of the Iranians were ordered by the judge hearing the case on 9 November 2006. The abovementioned brief contains a list of significant previous cases and numerous regulations that enable said recourse. The negotiations between the Islamic Republic of Iran and the Argentine Republic, which resulted in the signature of the Memorandum of Understanding of 27 January 2013, created, in Mr. Alberto Nisman’s view, a scenario that was contrary to the recourse that he intended to pursue, as his proposal of an approach involving mandatory measures was somehow against the agreement that had been reached. As a consequence, he decided to postpone the filing of this alternative and instructed that two documents be prepared based on the original approach. The first of them was prepared in case the Islamic Republic of Iran ratified the abovementioned memorandum. The second was prepared in case such ratification did not occur. Both request to declare the unconstitutional nature of the Memorandum of Understanding and its enacting law —which is still in progress—, as well as the preparation of the accusation that was finally filed on 14 January 2015 with Court No. 4 in Federal Criminal and Correctional Matters, Clerk’s Office No. 8, were supervening circumstances to the first drafts of these documents. Although, as instructed by Mr. Alberto Nisman, they were updated on several occasions, according to him the documents were outdated as his conviction in respect of a number of presumptions and conclusions contained in those texts had substantially changed, which is why he deemed it necessary to amend them once more so that they reflected his firm and current convictions. This is what Mr. Nisman explained to his Secretaries and to the undersigned. However, in the event of any contingencies, Mr. Nisman had signed two drafts, one in case the agreement was ratified by Iran, and another one in case such ratification did not occur. Both were dated December 2014, without specifying the exact day. Likewise, he also signed the last pages of each draft, which are dated January 2015, without specifying the day. On the other hand, as the drafts included an Annex made of photocopies, which comprised three hundred and eighteen (318) copies divided into two sets, he also signed a record to certify them, which is only dated 2014, without specifying the day or month. Finally, he signed two written communications asking for the intervention of the Argentine Attorney General so that the abovementioned proposal may be implemented. One of such documents is dated December 2014, while the other is dated January 2015; neither of the documents specifies the exact day.

Prosecutorial Unit, 28 January 2014.

[Signed]

Soledad I. Castro

Secretary of the General Prosecution Office

———————————————

Public Prosecutor’s Office

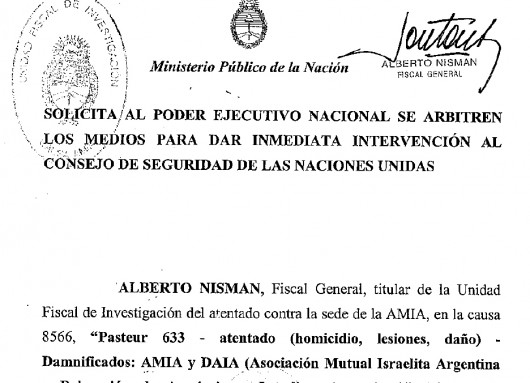

REQUEST FOR THE ARGENTINE EXECUTIVE TO TAKE IMMEDIATE MEASURES IN ORDER TO REQUIRE THAT THE SECURITY COUNCIL OF THE UNITED NATIONS TAKE STEPS

I, ALBERTO NISMAN, General Prosecutor in charge of the Prosecutorial Investigation Unit dealing with the bombings against the AMIA building —Case No. 8566 “Pasteur 633 – atentado (homicidio, lesiones, daño) – Damnificados: AMIA y DAIA (Asociación Mutual Israelita Argentina y Delegación de Asociaciones Israelitas Argentinas)” [on the bombings (homicide, injuries and damage)] heard by Court No. 6 in Federal Criminal and Correctional Matters for the City of Buenos Aires, Clerk’s Office No. 11 (AMIA Annex)— hereby state as follows:

More than seven years have passed since the General Assembly of the International Criminal Police Organization (INTERPOL) ordered that maximum priority be given to the search and arrest for extradition purposes (red notices) of five Iranian nationals accused in this case of having been involved in the AMIA bombings and still none of them could be interrogated thus far.

This unfortunate situation was and continues to be the result of the permanent and unchanging position adopted by the Iranian government, which has chosen to protect the persons accused of having participated in the bombings against the AMIA building, thus giving them, in practice, complete impunity, which they have been enjoying to this date.

Not even the addresses delivered by former President, Mr. Nestor Kirchner, and the current President, Mrs. Cristina Fernandez, before the General Assembly of the United Nations could overcome the reluctance of the Iranian government to arrest and extradite the accused, in spite of the fact that the intensity of the requests made by the Argentine government diminished over time due to Iran’s persistent refusals.

Indeed, Argentina went from simple requests for arrest and respect for Argentina’s jurisdiction to an offer to hold a trial in a third “impartial” country and, finally, to the execution of a “Memorandum of Understanding” that cannot satisfy the demands for justice and is inconsistent with the standards of local procedural law.

Notwithstanding the foregoing, the truth is that, throughout those years, the Islamic Republic of Iran has refused to extradite the accused, has rejected all requests for judicial cooperation made, has attempted to negotiate the provision of information in exchange for obtaining the disassociation of its nationals from the case, and its officials have repeatedly made statements with a view to discrediting the measures taken by the Argentine courts. In sum, the Iranian government adopted countless delaying tactics, the sole purpose of which was to simulate alleged cooperation which, in fact, never existed.

This attitude was even identified and repeatedly notified in the reports prepared by Human Rights Watch, a prestigious organization that has been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

The latest expression of this premeditated strategy by the Islamic Republic of Iran to give protection and impunity was the execution of the “Memorandum of Understanding”, an instrument that is legally useless to attain the main procedural goal of this investigation; that is, the arrest and subsequent prosecution of the accused.

That is, in a nutshell, the current situation of the proceedings. Thus far, there has been no change whatsoever in the historical position of rejection, hindrance and delay adopted by the Islamic Republic of Iran, as a result of which this Prosecutorial Unit decided to analyze the available legal tools that have sufficient force to overcome Iran’s failure to meet its procedural obligations.

Thus, a thorough analysis of various domestic and international laws, legal theses and precedents —as well as international arbitrations and decisions settling international disputes between nations— has led us to the conclusion that both the Islamic Republic of Iran and the Argentine Republic —as a result of the way in which the international community is organized— are part of the international and multilateral organization par excellence: the United Nations, of which both countries are Member States and to whose provisions they are subject.

A key aspect in this regard is the fact that the resolutions adopted by the UN Security Council are not only binding upon its Member States, but also, if not complied with, they may be compulsorily enforced by the Council.

As a matter of fact, the analysis carried out by this Prosecutorial Unit has shown that the Islamic Republic of Iran, through its refusal to judicially cooperate with the Argentine Republic in a case of international terrorism, is already in breach of its international obligations.

In view of the foregoing, the next step in the analysis was to establish what measure should be adopted in the face of the breach of international obligations by the Iranian government. This led to the finding of two precedents whose factual basis is identical to that of this case —that is, a country that harbours and protects persons accused of acts of international terrorism— and in which the efficient and concrete actions of the United Nations played an essential role.

These precedents refer to the situations involving the State of Libya and the Republic of Sudan which, at that time, also harboured —as the Islamic Republic of Iran does now— individuals accused of participating in terrorist actions.

In those cases, the UN Security Council, at the express request of the governments of the affected countries, passed resolutions requiring both Libya and Sudan to meet their international obligation to provide maximum cooperation in cases of international terrorism. In the face of the initial refusal by the required States, progressive sanctions were imposed which, in the end, produced a positive result, since both countries finally agreed to comply with the resolutions passed by the international organization, either through the arrest and subsequent delivery of the accused for prosecution or through the decision not to continue to provide the protection that, until then, the sanctioned State had been offering.

Considering that the attitude adopted by the Iranian government is exactly the same as the one taken in the abovementioned precedents and that Iran is already in breach of international obligations requiring cooperation in the fight against terrorism, it is safe to assume that the UN Security Council will adopt equivalent resolutions in the light of analogous situations.

This is no less than the legal solution to Iran’s outrageous reluctance and it not only contributes to satisfying the legitimate demand for justice of the victims of the attack and their relatives, but it is also consistent with the requests repeatedly made by the Argentine Government since 2007.

Therefore, resorting to the UN Security Council in order to request it to adopt a resolution ordering that the Islamic Republic of Iran arrest the accused for their subsequent prosecution and, in case of failure by Iran to do so, to enforce such resolution coercively is, in my opinion, an immediate and unavoidable obligation of the Argentine State.

On 18 July 1994, at approximately 9.53 a.m., a Renault Trafic van loaded with an approximate amount —equivalent in TNT— of between 300 and 400 kilos of a compound of ammonium nitrate, aluminium, a heavy hydrocarbon, TNT, and nitroglycerin, exploded opposite the building located in Pasteur street, No. 633, of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, which housed, among other institutions, the Argentine Jewish Mutual Association (AMIA) and the Delegation of Argentine-Israeli Associations (DAIA). The explosion caused the collapse of the front part of the building, which killed eighty-five people, injured at least one hundred and fifty-one to varying degrees, and produced considerable material damages within a radius of approximately two hundred meters.

Based on the report issued by this Prosecutorial Unit on 25 October 2006 (pp. 122.338/122.738) and the decision rendered by the Judge of the case on 9 November 2006 (pp. 122.775/122.800), the Argentine court ordered the initial interrogation of the following persons, for which purpose it issued a national and international arrest warrant against them: Ali Akbar Hashemi Bahramaie Rafsanjani (then President of the Islamic Republic of Iran), Ali Fallahijan (then Minister of Information of Iran), Ali Akbar Velayati (then Minister of Foreign Affairs of Iran), Mohsen Rezai (then in charge of the “Pasdaran” Revolutionary Guard Corps), Ahmad Vahidi (then in charge of the elite force “Al Quds”, which was part of the Revolutionary Guard), Mohsen Rabbani (then Cultural Counsellor of the Iranian Embassy in our country), Ahmad Reza Asghari or Mohsen Randjbaran (then Third Secretary of the Iranian diplomatic representation in our country), and Hadi Soleimanpour (then Ambassador of the Islamic Republic of Iran in Buenos Aires). Furthermore, the Judge held that the crime under investigation constituted a crime against humanity (Arts. II and III of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide and Arts. 6 and 7 of the Statute of the International Criminal Court).

The relevance of the international arrest warrants issued by the Judge was challenged —within the framework of the International Criminal Police Organization (INTERPOL)— by the National Central Bureau in Tehran, Islamic Republic of Iran.

In view of that situation, the Interpol General Secretariat summoned the parties to a meeting scheduled for 22 January 2007 in the city of Lyon, France. Delegates from Argentina and Iran participated in that meeting. On that occasion, the Argentine delegation —of which the undersigned was a member and the speaker— provided solid arguments to secure the registration of new “red notices” and urged the authorities of that organization to immediately order the search and arrest of those considered to be responsible for the bombings.

After hearing the arguments of the Iranian delegation, the Interpol General Secretariat ordered that the matter be heard by the Executive Committee of the organization, and tasked the Office of Legal Affairs with the preparation of a report on the issue being discussed.

The conclusion reached by the legal advisors of INTERPOL —and confirmed by the Secretary-General of such organization— was that maximum priority was to be given to the search of five accused Iranian nationals through a “red notice”. With respect to the arguments presented at the meeting held in Lyon, the report stated that “the highly professional explanation of the case, considering one accused at a time, provided by the Argentine prosecutors involved in the case was important for the Office of Legal Affairs to reach its conclusion, namely, that the case of the red notices request by the NCB Buenos Aires was not of a predominantly political nature so as to justify the application of the prohibition of article 3 [of the Constitution of the International Criminal Police Organization – INTERPOL]”.

The Executive Committee unanimously decided to follow the recommendations made by both the Office of Legal Affairs and the Secretary-General of the Organization and ordered, on 14 March 2007, the registration of the abovementioned “red notices”, but stated that if any of the NCBs involved in the dispute filed an appeal, the matter would be submitted to the General Assembly of the Organization for consideration. The General Assembly was scheduled to meet in the city of Marrakech, Kingdom of Morocco, in November 2007.

The appeal filed by the National Central Office located at Teheran was, in sum, what took the controversy to the organization’s General Assembly held on 7 November 2007, in which I participated as part of the Argentine delegation.

On that occasion, the Argentine position was approved by 78 votes to 14, with 26 abstentions. Thus, the International Criminal Police Organization’s governing body fully subscribed the position put forward by the Argentine delegation and consequently issued “red notices” for Iranian nationals Ali Fallahijan, Mohsen Rezai, Ahmad Vahidi, Mohsen Rabbani and Ahmad Reza Asghari.

This international approval not only put the investigation back on track but also ratified the restoration of the international community’s trust in the Argentine judiciary’s performance, integrity and efficiency with regard to this case.

Henceforth, the judiciary, the victims’ relatives, and the Argentine government’s goal was to have the indictees arrested in order to prosecute them, with all the guarantees provided for by the Argentine Constitution.

Three:

Argentina’s highest authorities–first Mr. Nestor Kirchner and afterwards Mrs. Cristina Kirchner– took before the United Nations the Argentine request for the Islamic Republic of Iran to submit to the Argentine jurisdiction and allow those accused of having taken part in the bombings to be brought to the Argentine courts. By doing so, they were clearly supporting the findings of this Prosecutorial Investigation Unit and the rulings of the court hearing the case.

Indeed, in 2007, Mr. Kirchner requested that “the Islamic Republic of Iran, under the applicable international law, accept and respect the jurisdiction of the Argentine courts, and cooperate with the Argentine judges to prosecute those accused of committing those crimes.» Additionally, he condemned Iran’s failure to cooperate in the following terms: «I wish to state here, at the United Nations, and before the rest of the countries in the world, that, to date, unfortunately, the Islamic Republic of Iran has not offered all the cooperation which was required by the Argentine judiciary to find out the truth about the bombings.»

Moreover, Mr. Kirchner appealed to the Secretary-General of the United Nations and all the countries in the world in order for them to intercede with Iran to process the arrest warrants. Thus, he pointed out that “we do so to pursue our only goal: to find out the truth and prosecute those responsible … Respect for memory (…) requires that justice be done» (Speech delivered at the 62nd Session of the General Assembly of the United Nations, New York, 25 September 2007, A/62/PV.5”.)

Mrs Cristina Fernandez, speaking at the UN in 2008, stated that: “…I hereby ask the Islamic Republic of Iran, pursuant to the rules of international law, to allow the Argentine courts to have the Iranian indictees tried in public, transparent trials with all the guarantees offered by a democratic system (…)In my country, those citizens will have a fair, public oral trial, with all the guarantees provided for by the Argentine laws in force and the supervision of the international community —which is inevitable as well as very positive in light of the seriousness of the events—, which provides the Islamic Republic of Iran with guarantees of fairness, justice and truth in the trial».

Next, Mrs Kirchner pointed out that «For that reason, I urge you once again to satisfy the Argentine judiciary’s claim —pursuant to international law and essentially because our attitudes to ensure access to justice all vouch for our respect for truth, justice and liberties—, which was accepted by Interpol and will undoubtedly contributed to find out the truth for everyone, not only for Argentinians, but for the entire world, at times when the values of truth and justice are lacking at an international level” (speech delivered at the 63rd Session of the UN General Assembly, New York, 23 September 2008, A/63/PV.5).

In 2009, Mrs Kirchner addressed the UN General Assembly thus: “In 2007, the then President [Nestor] Kirchner asked Iran, before this General Assembly, to allow Iranian government officials sought after by the Argentine courts to be extradited in order to conduct a thorough investigation and ascertain liability in connection with the bombings. Last year, right here, I once again requested the authorities of the Islamic Republic of Iran to satisfy Argentina’s request, making clear that constitutional guarantees apply in Argentina, that the principle that everyone is presumed innocent until proven guilty under a final judgment of a court of law applies throughout the country, that there are guarantees of freedom and justice administration. However, none of that happened; rather, this year, precisely one of the officials whose extradition had been required by the prosecutor leading the investigation has been given a ministry.»

In that same speech, the President held that: “… as President of the Argentine Republic, I will restate once again Argentina’s request for the extradition of the officials accused by the Argentine judiciary, not so that they can be convicted but so that they can be tried, relying on all the rights and guarantees enjoyed by all Argentine and foreign citizens in Argentina, which rights are secured by democracy and by a government that has turned the unrestricted defence of human rights into its institutional and historical DNA” (speech delivered at the 64th Session of the UN General Assembly, New York, 23 September 2009, A/64/PV.4).

But in her 2010 speech before the UN, in light of the fact that the Argentine claims had not been satisfied, Mrs Kirchner pointed out that “This time I will not request for a fourth time something that will clearly not be granted. Instead, given that it does not trust the Argentine courts because they are allegedly biased and they will not be disinterested enough to try the suspects, I will offer the Islamic Republic of Iran to choose by mutual agreement another country where the guarantees of due process are in place, where international observers can participate, where delegates of the UN can participate in order to prosecute those responsible for the outrageous bombing of the Jewish organization in Argentina.” (Speech delivered at the 65th Session of the UN General Assembly, New York, 24 September 2010, A/65/PV.14).

In 2011, Mrs Kirchner made public before the General Assembly a message from the Iranian foreign ministry expressing its intention to cooperate and engage in constructive talks with Argentina in order to find out the truth about the bombings. According to the president, the message in itself did not «satisfy our requests, which, as I have clearly stated, pursue justice». She stated that Argentina could not and ought not to reject the offer to engage in dialogue, but that it «did not imply that the Republic of Argentina should waive its claims originated in its judiciary in connection with the prosecution of the bombings suspects. Furthermore, we could not do it, because it lies within the province of judges and prosecutors to do it.” Furthermore, she added that the dialogue should be constructive and sincere and not a “delaying tactic or a diversion” (Speech delivered at the 66th Session of the UN General Assembly, New York, 21 September 2011, A/66/PV.11).

The year 2012 came and no cooperation actually occurred. Once again, at the annual session of the General Assembly of the United Nations, Mrs Kirchner referred to the AMIA issue. On that occasion, she said she had been requested by Iran to have a bilateral meeting between the Foreign Ministries of both countries, and stated that Iran had voiced its desire to cooperate with finding out the truth about the bombings. She spoke of concrete results and said verbatim, that: «If the Islamic Republic of Iran proposes to channel the issue into a path other than that proposed by Argentina, (…) as a member of a representative, republican and federal country, I will submit Iran’s proposal to the consideration of the political parties represented in the Argentine Congress. This is too important an issue to be left to the Executive only, even though the Argentine constitution vests the Executive with the power to represent the country and manage foreign relations. However, this is not a typical case of international relations, but an event that has deeply affected the history of Argentina and that adds a page to the history of world terrorism.”

Then, addressing the victims’ relatives, she added that “…I want you to rest assured, particularly the victims’ relatives, towards whom I feel deeply committed. I was member of the Full Committee in charge of following up on both bombings, that of the Embassy and that of the AMIA, for six years. I have always been very critical about the way the investigation was conducted, so I believe I am authorized to address the victims’ relatives, the ones who most need answers about what happened there and who was responsible, to tell them to rest assured that this President will take no action on any proposal put forward without previously consulting the victims…» (speech delivered at the 67th Session of the UN General Assembly, New York, 25 September 2012).

Furthermore, in the year 2013, the President of the Argentine Republic again made reference to the AMIA bombing during his speech at the 68th session of the General Assembly of the United Nations. It is worth noting that, by that time, not only had the “Memorandum of Understanding” between the Argentine and the Iranian governments already been signed, but also a particular situation had been face up that once again demonstrated the historic dilatory and obstructive position of the Iranian authorities on the question at stake, i.e., while in the Argentine Republic the memorandum had already been passed into law by the National Congress seven months before, the Islamic Republic of Iran had not yet officially notified to have reciprocated. Therefore, there were no grounds on which to base any exchange of diplomatic letters, a situation that would have led to deem the agreement in full force.

At that time, Cristina Fernandez pointed out that “…Now we wait they tell us if the agreement has been approved, when it will be approved if negative and if we can have a date of a line-up of the commission, a date so the Argentine judge can travel to Teheran […] I say this so in order that our deep conviction is neither mistaken with the norms of the International Right, nor mistaken our patience with ingenuousness or stupidity. We want answers; I believe that more than prudential time has gone by. The victims deserve it and I believe that very Islamic Republic of Iran deserves a chance to show the world that it would be different and that there are different actions” (Cristina Fernandez’ speech before the 68th Session of the General Assembly of the United Nations, on 24 September 2013, in New York).

Finally, in 2014, Mrs. President referred to the AMIA bombing again at the 69th Session of the General Assembly of the United Nations. At that time she stated that “…the government of President Kirchner was the one that had made the greatest efforts to find out who were the true responsibles, not only because it opened all the intelligence files of the country, and created the Special Prosecutorial Investigation Unit, but also because it was him who claimed in the year 2006 when the Judiciary of my country accused Iranian nationals to have perpetrated the AMIA bombing, he was the only president, then I followed him, who dared propose, demand the Islamic Republic of Iran, cooperation with the investigation. Cooperation has been demanded intermittently since 2007 and on in 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011 until the Islamic Republic of Iran finally replied—since before then, the issue could not even be included in the agenda—Iran agreed to have a bilateral meeting that later was effectively held and motivated the signing of a judicial cooperation memorandum of understanding between both countries. For what purpose? To have Iranian nationals accused of the attacks, and that of course live in Teheran, in the Islamic Republic of Iran, appear before the judge” (speech pronounced before the General Assembly of the United Nations, on 24 September 2014, in New York).

Also at that time, President Cristina Fernandez spoke at the meeting of the United Nations Security Council stating that “…in the year 2006, the Judiciary of my country, as a result of the creation of the Special Prosecutory Investigation Unit, promoted by President Kirchner for the purpose of thoroughly investigating the terrorist attack occurred—I reiterate—in 1994. Twenty years have gone by this year of that attack, but perpetrators have not yet been judged. The investigation, carried out by this prosecutor, has led the judge hearing the case to accuse Iranian nationals: 8 citizens living in Teheran. Since then, President Kirchner in the first place, and me, afterwards, as from the year 2007 to 2012, had requested at each one of the Assemblies held here, at the United Nations, cooperation of the Islamic Republic of Iran for us to be able to interrogate the nationals accused of the attack. Moreover, we had offered alternatives—as in the Lockerbie case—we offered the alternative to have a third country to judge them. Finally, in the year 2012, the Iranian Foreign Minister proposed us to have a bilateral meeting wherefrom—in the year 2013—the Judicial Cooperation Memorandum of Understanding between both countries resulted, with the sole purpose that the Iranian nationals appear before the judge hearing the case. Because, in my country, there is no regulation applicable by the Argentine judiciary allowing conviction in absence of defendant; instead, the accused shall be interrogated, shall be judged, pursuant to the principles of the Constitution and the fundamental rights.”

A careful understanding of the claims that have been put forward by Nestor Kirchner and Cristina Fernandez before the General Assembly of the United Nations since 2007 evidently show that the fundamental purpose of such request has initially been that the Islamic Republic of Iran have Iranian indictees accused of having perpetrated the AMIA bombing submit to the Argentine jurisdiction.

The Iranian unshakeable reluctance to honour this legitimate request has caused, in some way, to significantly erode the expectations of the Argentine Government in the last years; and, thus, claims brought afterwards have proved to be conditioned in such a manner that have led them to retract. In that sense, the proposal to have trial conducted at a third country before international overseers means, to a certain extent, that the initial claim has become more flexible.

Nonetheless, even at that instance, the goal pursued was that Iran would give up and submit indictees to our jurisdiction, i.e., our laws, our courts, and our investigation.

Finally, the abovementioned “memorandum of understanding” of 27 January 2013 diminishes the claims and circumscribes them to a goal that conspicuously downgrades that of the original claim with which Mr. Nestor Kirchner commenced this remarkable political decision of petitioning before the international community —through the legitimate and strategic use of the international fora and opinion— in order to expose Iran’s inadmissible position, thus turning international discredit into a legitimate pressure factor aimed at achieving the following goal: to prosecute the Iranian indictees in order to make progress towards bringing before the courts all the individuals legally responsible for the bombing of the AMIA building.

The sole purpose of this agreement can only be, in the best-case scenario, and provided its content is interpreted in a favourable light, to enable the Argentine judicial authorities to participate in an interrogation conducted in Iranian territory by the “truth commission”, which is created by such memorandum and made up —precisely— of representatives appointed by the Executive Branches of both countries. This Commission is authorized to interrogate only five out of the eight indictees, whose extradition has been denied by Iran. Within this framework, and bearing in mind the original claim made by Mr. Kirchner before the UN, the goal pursued by the memorandum has been conspicuously downgraded, but is not necessarily more feasible.

In this regard, the powers and the purpose of the commission constitute an unacceptable interference of the Executive into the exclusive field of the Judiciary, a challenge to the democratic and republican institutions, and an infringement of the basic principles set forth by the Argentine Constitution.

It is essential to point out that, ever since the commencement of the investigation, and in spite of the official statements made by the Islamic Republic of Iran by means of which it expressed its will to cooperate with the Argentine Judiciary, the Iranian regime did not cooperate in any manner whatsoever. On the contrary, when specific requests for judicial assistance were delivered to it, the Persian government’s response has always been to hinder the procedure and to adopt a conspicuously delaying, provocative, and challenging position while unwontedly stating that it was willing to provide assistance to our country in the investigation of the bombing.

This double discourse was exposed on several occasions, of which undoubtedly the most emblematic was the proposal made by Iranian officials through a document called “non paper”, by means of which they offered all the necessary cooperation to the Argentine authorities on the absurd condition that, in exchange, no accusations be filed against Iranian citizens.

It goes without saying that, on that occasion, such an offer was rejected, as it meant subjecting the required judicial assistance to the condition of guaranteeing impunity to those who, according to the evidence, were involved in the bombing. The condition proposed by the Iranian political authorities was and is unacceptable within the framework of a State based on the rule of law. Moreover, it constitutes a challenge to the jurisdictional activity that stems from Argentine sovereignty.

It is clear then that the Islamic Republic of Iran has maintained, throughout the years, an unwavering obstructive attitude, which was mainly evidenced by its categorical denial of the detention for extradition of those individuals who were accused by the Argentine Judiciary on account of their liability for the bombing of the AMIA building. This obstructive conduct stems from Iran’s political decision to hinder the investigation, and constitutes a previously-designed strategy whose sole purpose is to prevent its citizens from being prosecuted.

The position adopted by the Iranian government, which consists in obstructing and hindering the investigation and discrediting the activity of the Argentine Judiciary, has remained unaltered over the years.

This lack of cooperation was also noticed by the Human Rights Watch (HRW)[1] organization, which was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. The organization has repeatedly expressed its concern about how Iran’s attitude has contributed to hindering the investigation (annual reports for 2011 and 2012). The Director of the Americas Division of this prestigious organization, Jose Manuel Vivanco, was even more categorical when he stated, in relation to this matter, that Iran “has not contributed with the investigation in progress until now” (pp. 11947/11948 of dossier 263).

The abovementioned shows that not even being exposed to the international community by the accusations of a renowned non-governmental organization in respect of the obstruction of the Argentine investigation by the Islamic Republic of Iran has altered Iran’s position in this matter.

Year after year, Iran adopted a challenging attitude, even when faced with the claims made by Mr. Kirchner and Ms. Fernandez respectively before the United Nations. This attitude was expressed through the delivery of letters to the President of the General Assembly of that organization by the Permanent Representative of the Islamic Republic of Iran to the UN, Ambassador Mohammad Khazaee.

In those letters, he claimed that the accusations against the Iranian nationals were false and that it was necessary to find and punish the true culprits. Moreover, the investigation of the Argentine Judiciary was discredited (see official letters sent by Ambassador Mohammad Khazaee, Permanent Representative of the Islamic Republic of Iran to the United Nations, to the President of the General Assembly on 28 September 2007, 2008, 2009, and 2010).

The discrediting statements made by the Iranians went as far as to accuse the Argentine government of “engaging with terrorist groups, particularly with the notorious Muyahidin Jalk organization (…). It is also responsible for its financial support to this terrorist group and for the payment of bribes to induce fabricated testimonies against Iranian citizens”. The Argentine government was also accused of being “responsible for the terrorist attack against the former Iranian chargé d’affaires in Buenos Aires in 1995” (letter of 28 September 2010).

Another example that evidences that the Islamic Republic of Iran never had the intention of cooperating with the investigation in any manner whatsoever were the statements of the then spokesman and current Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs for Legal and International Matters, Abbas Araqchi, who held that “foreign agents are behind the AMIA incident”. In addition to this statement, which seriously diminishes the brutal attack, he said that “the case is currently subject to a normal procedure” (11943/11944 of dossier 263). In view of the above, Iran considers that the procedure established by the memorandum of understanding constitutes a “normal” one, and once more disregards, as it always has, the activity and the conclusions of the Argentine Judiciary.

Recently, the abovementioned official made statements aimed at discrediting the Argentine judicial investigation, which in his words is “tainted” by the “intrusion of the Zionist regime” (p. 11945 of dossier 263).

This having been stated, in order to get an accurate idea of the conspicuous lack of cooperation of the Islamic Republic of Iran, there follows a detailed description of the different forms that such lack of cooperation adopted, either by frustrating requests for judicial assistance issued within the framework of the case or by rejecting the requests for extradition.

b.1) The requests for judicial assistance were frustrated by Iran

Within the framework of this investigation, judicial assistance has been requested to the Islamic Republic of Iran on repeated occasions in order to obtain information both on certain individuals and on telephone lines, immigration records, bank accounts, and properties in that country.

The attitude adopted by the Iranian authorities in this regard was invariably characterized by their denial to cooperate, the delay in their responses, the attempt to secure the impunity of their nationals, and even the unwonted condition of providing information in exchange for dropping all the suspicions against the citizens of their country.

In respect of this aspect in particular, on 3 April 2005, the Argentine Republic’s Chargé d’Affaires in Iran delivered a new letters rogatory in relation to the case to the Head of the Department of International Law Affairs of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of that country. On such occasion, the Iranian official stated the following conditions in order to answer the letters rogatory: “…If we provide our assistance to the Argentine Judiciary: a) Would not we be seen as the accused or the suspects? b) Suppose that we receive the letters rogatory and answer them […] Will the judge be ready to announce and categorically declare that there is no connection between Iran or its citizens and the AMIA bombings? c) Will the dossier remain open or not if we answer? d) How can we know whether the judge will close the dossier or not?”

He added: “the main issue is that, somehow, we need to be certain that, if we do cooperate, the judge hearing the case will reach the conclusion that Mr. X or Mr. Y are not, and were not, involved in the AMIA bombings. Remember that, since 19 July 1994, we have been stating that we are willing to cooperate with the Argentine Judiciary, and this position and offer are valid up to this day. If we had objective guarantees, tangible facts (tangible results), we would have no problem: a) receiving all letters rogatory; b) answering all such letters; c) even more: conducting some additional investigation in Iran…” (pp. 116.381/116.383).

The same rhetoric was repeated by the Iranian officials at the meeting held in Tehran in July 2005 between diplomatic representatives of our country and the local Head of International Law Affairs, Mr. Mohsen Baharvand, in relation to the letters rogatory whose receipt and answer by the Iranian Judiciary were pending.

On such occasion, the Iranian official said: “We need that prospect to receive and answer the letters rogatory. Bear in mind that these are Iranian government officials and not ordinary citizens; in all, whenever one has something to give, one is expecting to receive something as well (…) The Iranian side is very flexible with the letters rogatory. We only complicate things when it is absolutely necessary (sic), and that is not the case of our relation with Argentina” (pp. 117.251/117.253).

Another example of Iran’s attitude in relation to its cooperation in the case is provided by a “non paper” delivered by the abovementioned Baharvand to Argentine diplomats with an agreement proposal between both countries (pp. 118.680, 118.952/118.953 bis).

The agreement then offered by Iran said the following: “1. The parties agree that there have been no accusations against Iranian citizens in relation to the AMIA case. Notwithstanding the foregoing, the proceeding being conducted by the Argentine judge in charge of the investigation has been ordered, in respect of the Iranian citizens, for the sole purpose of gathering information.”

“2. The parties… shall abstain from making any kind of criminal implications, either directly or indirectly, or accusations against the other party and its officials.”

“3. The letters rogatory issued by the Argentine Judge shall be amended so that no affirmations or accusations are made, whether explicitly or impliedly, against the Iranian government and its citizens…”

“4. Once the provisions of the third paragraph have been observed, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Iran shall officially receive the letters rogatory…”

“5. The Argentine side… shall remove any arrest warrants issued by the Judge in charge of the investigation against citizens of the Islamic Republic of Iran…”.

The brief account made here reveals the unwonted position adopted by the Iranian government, which consists in subjecting their cooperation to a commitment by the Argentine judicial authorities not to accuse the officials and/or citizens of that country.

On the other hand, on account of two requests aimed at obtaining information on holders of telephone lines, the Iranian authorities, through Interpol Tehran, answered the first request as follows:

“we are unable to comply with your request due to the importance of observing human rights principles and rules, and also Iranian domestic laws concerning respect for personal private life” (folio 908, record 391). The other request, far from providing the requested information, only stated: “ … please explain the reason and also inform where you obtained these telephone numbers …” (folio 6843, record 201).

With this, we can only consider that the excuses made up by the Iranian government, in order not to answer the Argentine requests, are absurd and ridiculous, which is aggravated by the fact that, although the requested details were later sent to Tehran, even so we were unable to obtain a reply.

As regards the diplomatic letters rogatory delivered to the Republic of Iran in these proceedings, they were the following: a) letter rogatory of June 27, 2000 (pp. 550/551 in record 204); b) three letters rogatory dated March 5, 2003 (pp. 106,475/76, 106,479/80 and 106,481/82); c) one letter rogatory of May 16, 2003 (pp. 108,201/02; d) one letter rogatory of September 19, 2003 (pp. 1235/1239 of record 402); e) letter rogatory of May 4, 2004 (pp. 3409/3413 of record 402); f) letter rogatory of April 9, 2007 (pp. 124,239/124,242); g) letter rogatory dated May 16, 2007 (pp. 910/913 of record 391); h) another letter rogatory of June 6, 2007 (pp. 6832/6836 of record 201); i) letter rogatory ordered on October 9, 2007 (pp. 3969/3974 of record 402); j) request for assistance of October 3, 2008 (pp. 6020/6023 of record 204); k) letter rogatory of October 29, 2008 (auxiliary record related to civil action, pp. 79/88); l) letters rogatory of April 30 and August 12, 2009 (auxiliary record related to preventive attachment, pp. 118/121 and 134/138); m) letter rogatory of February 2, 2012 (pp. 1170 of record 415); and n) letter rogatory of February 14, 2012 (folio 6416 of record 392).

Of these seventeen requests, the government of the Islamic Republic of Iran only replied to one (pp. 126,761/126,779 and 127,614/127,657). Also, this one reply, of a merely formal nature, was, strictly speaking, a flat refusal to provide the requested judicial assistance.

Indeed, in this reply from the Tehran prosecutor Mr. Rumiani, he stated that the requirements for judicial cooperation with Tehran could only be feasible if they complied with certain minimum formal and substantive legal requirements, which arise from international and comparative law. However, he failed to indicate the international and/or comparative law instruments or custom prescribing the requirements that were allegedly not fulfilled. This was a malicious omission, because prosecutor Rumiani’s requirements are in no way consistent with international practice on the subject of penal cooperation.

Specifically, the Iranian prosecutor’s office declined to provide judicial assistance based upon the absence of a reciprocity offer, an alleged violation of the presumption of innocence and an inadequate assessment of the evidence.

All such allegations are untrue, and their lack of support shows a strategy seeking to protect these persons accused of participating in terrorist actions.

The Iranian prosecutor alleged that a request for judicial assistance could only be complied with for reasons of courtesy and international reciprocity. He stated that the International Cooperation Law of his country (approved in the year 1309 of the Persian calendar, equivalent to the year 1931), grants judicial assistance on condition of a specific offer of reciprocity, adding that “the letters rogatory issued in these proceedings did not include any transcript or translation of the relevant legal provisions in Argentina, evidencing reciprocity as a basis for judicial assistance” (pp. 126,716 and 127,617).

However, Argentine law not only provides for reciprocity as a rule for international cooperation (section 3 of the Law No. 24,767), whereby Argentina is bound to offer any requesting State ample assistance in relation to the investigation, trial and punishment of criminal offences (section 1 of such Argentine law), but also, pursuant to such legal provisions, the wording of absolutely all the letters rogatory addressed to the Islamic Republic of Iran specifically include an offer of reciprocity by our country. That is, the Argentine Republic has specifically offered the Iranian authorities most ample reciprocity. This simply cannot be denied. It is written in all the letters rogatory delivered to Iran. Finally: the offer of reciprocity is a requirement that has been abundantly fulfilled.

As to the insinuation that the Argentine Judiciary failed to observe the presumption of innocence, all we need to clarify is that the accusation by this Prosecutorial Unit (pp. 122,338/122,738) and the decision of the Judge in these proceedings, Mr. Rodolfo Canicoba Corral, to call the accused to a hearing in order to hear the charges (pp. 122,775/122,800) is not a violation of the presumption of innocence, but quite the opposite. It shows the right of an accused to raise a substantive defense against the accusation, and provide his/her version of the events if the accused wishes to do so. It is the primary act of defense in the Argentine procedural system (articles 18 of the National Constitution and sections 294 and associated provisions in the National Code of Criminal Procedure).

Thus, it is clear that the Iranian prosecutor’s office incurred in an obvious conceptual error about the procedural steps in the Argentine judicial system, and tried, based upon such error, to find grounds in order to reject the request for judicial assistance.

Finally, neither can we accept the Iranian prosecutor’s attempt to assess the evidence, in a manner intended to justify his dismissal of the request for judicial assistance. It cannot be seriously said that, in order to comply with a request for judicial assistance, the requested party must assess the evidence and dismiss the petition, based upon the circumstance that its judicial authorities do not agree with the assessment conducted by the requesting country, and even less so where the requests are for simple actions – such as the requests made to the Islamic Republic of Iran in this investigation– .

As conclusion, the inconsistency of each allegation made by the Tehran prosecutor, so as to dismiss the judicial assistance requested by the Argentine Republic, clearly shows that the decision not to cooperate with the investigation in the AMIA case has nothing to do with legal reasons.

On the contrary, the Islamic Republic of Iran is disguising its protection of persons accused of an international terrorist action, with its misrepresentation of legal arguments –which are easily refuted, as in the above paragraphs –, in an attempt to show that Argentina has failed to observe a number of requirements, and so justify its premeditated lack of cooperation. It is then a uniform type of reply which, I repeat, was already determined beforehand, and repeated in other attacks where Iranian officers have been accused of terrorist actions (the ‘Mykonos’ case, for instance), so it becomes apparent that the purpose of such obstruction of justice is to protect the Iranian accused.

b.2) Declined extradition: dismissal of a request for provisional detention submitted by the Argentine judiciary

On November 9, 2006, the Argentine judiciary issued a letter rogatory to the Court in the Islamic Republic of Iran having competent jurisdiction on the subject, for provisional detention, contemplating future extradition, of Ali Akbar Hashemi Bahramaie Rafsanjani, Ali Fallahijan, Ali Akbar Velayati, Mohsen Rezai, Ahmad Vahidi, Mohsen Rabbani, Ahmad Reza Asghari or Mohsen Randjbaran and Hadi Soleimanpour.

At the time of the request, the Judge Rodolfo Canicoba Corral – under the Law No. 24,767- specifically offered the Iranian counter-party reciprocity for analogous cases.

The letter rogatory addressed to Iran was delivered by diplomatic channels and, upon being reviewed, on October 4, 2008 the Public and Revolutionary Court in Tehran dismissed the letter rogatory issued by the Argentine judiciary, upon mistakenly considering it as a request for extradition (pp. 127,063/127,080 and 128,205/128,220).

Below we review the grounds alleged in order to dismiss the petition from the Argentine judiciary.

This review, once again, will clearly show the unconcealable fact that the dismissal is not based on legal grounds, but that such grounds are rather a way or cloaking the true intention of the government of Iran: endeavoring to provide impunity for those accused of terrorism for their involvement in the attack conducted on Argentine soil, with abuse of international law provisions governing the extradition of persons between States.

In this way, a knowledge of the untrue Iranian allegations, their profound weaknesses and their result: that is, protecting the Iranian accused in these proceedings, will contribute to provide a clear understanding – as already said above – of the need to resort to international institutions (United Nations Organization) so as to try to remove the obstacles placed by the Islamic Republic of Iran to the delivery of the accused, which has – so far– hindered the progress of the proceedings on this particular matter.

The refusal to comply with a request for provisional detention of the accused, erroneously considered by the relevant Persian courts as a request for extradition, since it was a petition for provisional detention in order to make possible a future request for extradition, is based upon a number of grounds, as follows: a) priority of Iranian domestic laws; b) prohibition to extradite nationals; c) immunity of political, diplomatic and military authorities; d) insufficiency of evidence; e) inapplicability of the Treaty of Rome to the case; and f) unavailability of assurance of a fair and impartial proceeding. Each of such arguments will be discussed below.

b.2.a) Priority of domestic laws of the Islamic Republic of Iran

Prosecutor Rumiani said that, absent any bilateral and/or multilateral treaties directly binding the Argentine Republic with the Islamic Republic of Iran on the subject of extradition, the domestic laws of his country are the applicable legal system for the case.

In fact, he considered that the Criminal Extradition Law (approved in Persian year 1339, equivalent to 1960) applies to the case. Such law indicates that, in the absence of a treaty, extradition shall be based upon reciprocity. As indicated in the Iranian reply, section 1 of the law allows extradition if the legislative, judicial or even administrative procedures of the Argentine government offer reciprocity for the extradition of criminals. That is, according to the domestic law of Iran itself, the principle of reciprocity has priority and governs the extradition proceeding.

On this matter, the Iranian prosecutor stated that, according to his own research, the Argentine Republic does not have in place legislation that provides for the principle of reciprocity, so as to enable the acceptance of an incoming request for extradition, that is, a petition made by another country.

Nothing can be farther from reality. It has already been clearly evidenced that the Argentine Republic, from the beginning of this investigation, in each and every letter rogatory addressed to Iran – including the request for provisional detention of the accused – specifically offered reciprocity for analogous cases. Such offers were made in writing and were received by Iran, so they cannot be denied since there is evidence thereof throughout the record. It is surprising that a matter that can be so easily verified can be absurdly denied by the requested State, from which we can assume their bad faith. Finally, the truth is that the Argentine Republic has always offered the Islamic Republic of Iran ample reciprocity.

Likewise, and contrarily to what has been said in the Iranian reply, Argentine legislation has adopted the principle of reciprocity for cases of extradition, in the absence of a treaty. Thus, section 3 of the Law 24,767 reads: “In the absence of a treaty prescribing it, the assistance shall be subject to the existence of reciprocity or an offer thereof …”.

Moreover, this has been the policy of the Supreme Court of Argentina for more than a century, in holdings that have based the delivery of a criminal, absent a treaty, on the principle of reciprocity. To this end, it has held that: “… reciprocity and consistent practice among nations may only be asserted – or contested – in the absence of a treaty …” (CSJN, April 30, 1996, “Liendo Arriaga, Edgardo s/ extradición”, Fallos 319:510).

Finally, under Argentine rules of procedure (section 134 of the National Code of Criminal Procedure) there are also provisions contemplating the cases and manners in which a letter rogatory from a foreign court must be submitted, always subject to reciprocity.

From the above we may conclude that Argentine legislation has specific provisions contemplating the principle of reciprocity, a legal policy that has also been upheld since long ago by our highest court.

In summary, Argentina and Iran have not entered into a bilateral treaty on the subject of extradition. Neither are they parties to any multilateral agreement providing for this type of international assistance for cases such as the case investigated in these proceedings, for instance the Convention for the Suppression of Terrorist Bombings (New York, 1997) or the Convention for the Suppression of the Financing of Terrorism (New York, 1999), instruments including provisions whereby the States have the duty to provide mutual assistance. Suggestively, the Islamic Republic of Iran has not ratified these conventions, which would be most useful to bring the accused to trial.

Consequently, we must abide by the laws of the requested country. In this case, both Argentine and Iranian law are coincident where they prescribe that the matter is governed by the principle of reciprocity.

This objective legal fact shows that extradition is perfectly available, because the Argentine Republic has explicitly offered reciprocity. By consequence, alleging as the Iranian decision does, that reciprocity is not provided for by Argentine procedures, constitutes – as demonstrated above – an untenable allegation that does not withstand the slightest review, and is just another example of the rock-solid protection granted to those accused of bombing the AMIA building on July 18, 1994.

b.2.n) The prohibition to extradite nationals

In a second argument, Iran refuses to surrender its accused nationals on the grounds that, due to the absence of bilateral or multinational treaties and the alleged lack of reciprocity, it must refer to its internal legislation, which sets out the prohibition to extradite nationals (Article 8(1) of the Law on Extradition of Criminals).

As proved in the previous section, the Argentine Republic indeed offered reciprocity to its Iranian counterpart and it is precisely such principle of International Law that must govern the relations between both countries on this subject.

Notwithstanding the foregoing, we will make very few considerations that show, once again, how fragile the Iranian position is. In this sense, the reference to the “United Nations Model Treaty on Extradition” (signed in 1990, in New York), the European Extradition Convention (signed in 1957, in Paris) and the United Nations International Convention for the Suppression of the Financing of Terrorism (signed in 1999, in New York), provides the grounds for refusing the request as none of these international instruments, cited by the Iranian Party, imposes the prohibition to extradite nationals.

It should be noted that, pursuant to the text of the “Model Treaty” -which is not binding-, extradition of nationals is optional (one of its provisions reads: “…optional grounds for refusal…”). In addition, it must be mentioned that Iran has taken some provisions from the “Model Treaty” but has ignored others that provide for full judicial assistance.

The European Extradition Convention (be it noted that in practice said Convention is totally inapplicable to this case as neither Argentina nor Iran are located in the European continent) provides for the right to refuse extradition (Article 6), which means it is not an obligation, and, finally, the Terrorist Financing Convention, which, as previously mentioned, has not been ratified by the Islamic Republic of Iran, sets out the “possibility” of refusing extradition in certain cases.

Such legal inconsistency clearly shows that the Iranian system, in its attempt to obstruct the Argentine justice, is far from performing a serious and complete analysis of International Law as none of the abovementioned instruments support the position of the Iranian Prosecution; two of them do not even apply to its territory and as for the other, apart from the fact that it has no binding force, Iran partially uses its provisions, adopting the ones that conform to its interests and ignoring those that provide for the obligation to cooperate.

In sum, a national’s extradition is recognized as a right to act in a certain manner and may never bring with it the prohibition to act in a different way. Otherwise, the right of the States to opt to extradite their nationals would be violated. The reasonable conclusion is that extradition of nationals is a possibility, a power and a right of the States. This is shown by the abovementioned instruments in Iran’s own argumentation.

Thus, the study of the international agreements mentioned reflects that current customary international law relativizes the ancient principle of “no extradition of nationals”, the States having the power to refuse surrender of the person sought. Nowadays, the generalized and uniform practice among the States and the opinio juris sive necessitates seem to confer upon the requested State the power to extradite (or not) their fellow nationals, yet no rule in customary international law prohibits a State from deciding to extradite one of its nationals. Such power is further limited when a State must fulfill its obligations to cooperate in combating international terrorism, which, producing devastating effects in several countries, requires an extremely restrictive interpretation of the option to refuse to extradite a person accused of participating in such an offence.

Finally, it is important to mention that the Argentine Republic, since very early ages, has permitted extradition of its nationals. The principle of full custody of nationals that prevailed at the end of the nineteenth century has not been upheld by national legislation which, in its process of evolution towards a more universalist conception, started to sign agreements admitting that Argentine citizens may be brought to trial in a foreign country.[2] In fact, Argentina has signed agreements with countries such as Australia[3], Korea[4], Spain[5], Italy[6], Paraguay[7], the United Kingdom[8], and Brazil[9] providing for optional extradition of nationals. In addition, Argentina undertook to extradite its nationals in the instruments signed with Uruguay[10], Peru[11], and the United States[12].

Having clarified this point, it should be highlighted that Argentine internal legislation (Law No. 24767, which governs the subject) does not prohibit extradition of nationals and, in fact, the text of said law sets out its own subsidiary nature when it provides that: “…If a treaty has been signed between the requesting State and the Argentine Republic, its provisions shall govern the assistance procedure (…) All those situations not specifically contemplated in the treaty shall be governed by this law…” (Article 2 of Argentine Law No. 24767).

Lastly, the Iranian prosecutor intended to support his position by mentioning the refusal to extradite the Argentine former Navy Captain, Alfredo Astiz, now sentenced, to the French Republic. This case cannot be compared with the protection granted by Iran to its nationals because the crimes which Astiz was charged with had been committed in the Argentine territory and were being correctly tried in Argentine courts. Then, the refusal to extradite Astiz was not grounded on the decision not to extradite nationals -as was maliciously alleged- but on the primacy of the territoriality principle in the spatial scope of application of criminal law over that of nationality.

So, Iranian statements that the Argentine Republic has enshrined the principle of no extradition of nationals, that its internal legislation does not permit extradition of Argentine citizens and that such was the position that prevailed in the Astiz case are some more of the many cunning arguments made in order to refuse to surrender the accused with the intention of ensuring their impunity.

b.2.c) Immunity of political, diplomatic and military authorities

According to the third argument put forward in the Iranian decision, the arrest orders and the subsequent extradition of the persons requested turned out to be infeasible due to the fact that the accused are protected by a number of political, diplomatic, and military immunities, which shield them from the Argentine justice.

This issue has already been meticulously addressed by this prosecutorial unit in the decision dated 25 October 2006 (pp. 122.338/122.738) and we should refer to it in order to avoid unnecessary repetitions. It is worth emphasizing, though, that in such decision some concepts and essential documents were deeply analyzed when the immunity issue was dealt with, for example: the differences between personal and subject matter immunity; the implications of absolute immunity; discussions by legal scholars about the distinction between Head of State and Head of Government and the practical consequences of such labels; the distinction as regards immunity related to the type of Court hearing the case (national or international); the contents of the Convention on Special Missions[13] and the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Crimes against internationally protected persons, including diplomatic agents[14].

In accordance with the conclusions reached on that occasion, it was decided that the arrest of Ali Hosseini Khamenei, Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran, be requested. As for the other officials, namely, Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, Ali Akbar Velayati, Ali Fallahijan, Ahmad Vahidi, Mohsen Rezai, Mohsen Rabbani, Ahmad Asghari o Mohsen Randjbaran and Hadi Soleimanpour, who, when their arrest was requested, were no longer holding office as they did when the attack was carried out. Therefore, it was concluded without hesitation that they had no possibility of invoking immunity ratione personae from criminal jurisdiction in Argentine courts.

Likewise, they may not either allege residual immunity with the purpose of being exempted from liability when -although this is quite obvious- deciding, planning, and ordering the commission of a terrorist act in a third state is not within the scope of the duties that, pursuant to international law, are assigned to heads of government, ministers of foreign affairs, state officials, military leaders or diplomatic agents.

Indeed, while in office, immunity protects certain officers; once they are no longer in office, they are only protected where their competence is concerned. Having reached these conclusions in this case, please note that no indictees are any longer in office (as they were at the time), and that the type of conduct attributed to them (to be involved in an act of terrorism) can never be included in the notion of “official acts”. Clearly, thus, Iranian fugitives have no political, diplomatic or military immunity.

Regardless of the above, what is new here is the fact that international terrorism has been assimilated to a political crime. This has been stated in their response, when they invoked Article 3 of the Model Treaty on Extradition of the United Nations which states: “Extradition shall not be granted in any of the following circumstances: (a) If the offence for which extradition is requested is regarded by the requested State as an offence of a political nature;” The Islamic Republic of Iran, anxious to protect fugitives against whom an international arrest warrant has been issued as top priority, has gone as far as absurdly putting on the same level a terrorist attack and a political crime. This position is so gross that it actually calls for no response at all. Nevertheless, we will refute it for the sake of preventing this type of arguments in the future, whose aim is to avoid handing the accused over. Secondary authority and Case Law have agreed in that acts of terrorism cannot be considered “political or extraditable crimes”, even when this type of heinous acts may include some political components. Terrorism cannot enjoy the principle of no extraditability applicable to political crimes. Indeed, the Doctrine on which this exception was grounded was initially conceived as a protection of human rights and was never intended to safeguard those who attack Human Rights with open impunity.[15]” The was the opinion of Argentine Parliamentarians who in Section 9 of the Law of International Cooperation in Criminal Matters (24,767) excluded acts of terrorism from the concept of political crime, thus supporting and recognizing the international criteria in this respect. Finally, in order to settle this issue for once and for all, may we point out that several treaties signed by Argentina provide for “acts of terrorism”, but none of these treaties considers “acts of terrorism” political crimes[16]. b.2.d) Insufficient Evidence Reiterating the statements made by the Iranian prosecutor in the only response (a negative response, by the way) given by him to the seventeen requests for legal assistance issued by the Argentine Judiciary, upon denying provisional arrest pending the extradition of the indictees, the evidence included in this investigation was once more questioned. This was done in the understanding that the evidence collected in the AMIA case was not relevant enough or valid enough to support the accusation of those whose arrest was requested, and that the inexistence of robust legal grounds infringed the presumption of innocence, whereby extradition should be rejected. Interestingly enough, within the framework of the Argentine legal system, the accused are entitled to examine the evidence, to weigh it, match it with other evidence included in the investigation, submit new evidence, give their version of the facts, etc. Once the indictees have been lawfully made a party to the case and are under the Judge´s authority, any analysis of the lawfulness and robustness of evidence which may be carried out shall be reviewed by the Argentine Judiciary. This is the only legal and legitimate environment where all parties may present their vision of the facts under investigation and produce evidence to ground it. All in all, that is what defense at Court and due process mean, the only legal mechanism allowing justice to be done. Unfortunately, facts show that the Iranian party is not willing to undergo legal processes and, rather, has approached things in a wrong way, invoking judgments that are not applicable in this case, such as judgments about issues where the international responsibility of States is at stake (such as, for instance, “Bosnia Herzegovina v. Yugoslavia”, the “Corfu Channel Case” or “Nicaragua v. the United States”), and not where individual criminal responsibility is being tried. As we know, evidentiary standards in both cases are remarkably different. In consequence, the Iranian strategy shows up again, disguised as a legal argument, actually aimed at supporting an openly illegal political decision, i.e. to award impunity to the persons accused of terrorism. As regards the Case Law alleged by the Iranian Prosecutor, originated in the judgment “Corfu Channel Case: (the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland – Albania)”, clearly the decision in that case does not strengthen in the least that position, but, rather, it weakens it, clearly showing that evidence standards have been comprehensively met in this case and that they support the accusation made. Indeed, the Case Law invoked established that when the controls of a State prevent direct evidence to be submitted in connection with the facts, the State which is the victim may recourse to inferences of fact and circumstantial evidence; such indirect evidence must be regarded as of especial weight when based on a series of facts, linked together and leading logically to a single conclusion[17]. Precisely, that is why the Iranian position should be highlighted: on one hand, hindering and systematically preventing any type of legal assistance and, on the other hand, claiming that the evidence is insufficient. This is no surprise, really, as we are aware that such reluctance has been planned beforehand and that its only purpose is to complicate things so as not to turn over the indictees but rather to provide for their impunity. The Iranian Government has decided to protect them and to harbor them zealously, having even rewarded several of them by appointing them to high public positions. b.2.e) Impossibility of Enforcing the Rome Statute in This Case The argument of the unenforceability of the Rome Statute for the International Criminal Court vis-á-vis the provisional arrest request pending extradition requested by the Federal Judge presiding over the case, rests on false premises. Indeed, the Prosecutor´s Office in Teheran assumes, or supposes, that the Judge presiding over the case resorted to the provisions of the Rome Statute turning them into the grounds or into a supporting instrument to ground the arrest request pending extradition. Such interpretation is incorrect. Actually, it is enough to merely read the decision issued by Federal Judge Canicoba Corral on November 9, 2006. Indeed, such decision clearly establishes that, in line with Art. 6 and 7 of the Statute for an International Criminal Court, and Art. 2 and 3 of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, the AMIA bombings clearly are a crime against humanity. Indeed, in the first paragraph of the aforementioned decision, the Judge resolves: “I) DECLARING THAT THE CRIME UNDER INVESTIGATION IS A CRIME AGAINST HUMANITY, as provided for in the Section THREE (Articles I and III of the Convention for the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, and Articles 6 and 7 of the Statute for an International Criminal Court)” (pages 122.775 / 122.800). More specifically, an International Criminal Court will recourse to the Rome Statute exclusively on the basis of the facts under investigation and their legal consequences, the procedural aspects regarding the appearance of indictees is completely beside the point. Similarly, this also stems clearly from the letters rogatory issued by the Judge to the competent authorities in the Islamic Republic of Iran. In such instrument, Articles 6 and 7 of the Rome Statute were invoked under “Legal Description of the Facts under Investigation” (pages 122.823 / 122.827). In that decision, which in Section II provides for the issuance of such letters rogatory (a certified copy of which was attached to the letters rogatory in question), the Rome Statue was invoked together with a leading case which was quoted, namely the Argentine Supreme Court of Justice case: “Arancibia Clavel, Enrique Lautaro re. Aggravated Homicide, Conspiracy et al” dated August 24, 2004. It was precisely after that decision was issued by the highest Court of our country that the Rome Statute for the International Criminal Court began to be considered one of the instruments of International Law under which a crime may be considered a crime against humanity. Indeed, the Rome Statute addresses notions such as crime against humanity and genocide (among other crimes), already recognized in international common law and, in some cases, in conventional international law, resulting from the evolution of Case Law and Doctrine on international criminal law. Thus, such notions, embodied in the Statute, were already valid and applicable in Argentine Law before such international instrument was adopted. In short, having analyzed the decisions issued by the Federal Judge presiding over the case (which documents were also forwarded to the authorities of the Islamic Republic of Iran), it is clear that the Rome Statue for an International Criminal Court was not invoked in connection with the provisional arrest request pending extradition, but rather with the classification of the AMIA bombings as a crime against humanity, which classification was adopted by the Argentine Judiciary on the basis of current legal parameters and Case Law, pursuant to the provisions of national and international law applicable hereto.

b.2.f) Lack of guarantee of fair and impartial trial

The last of the arguments of Tehran’s prosecutor to deny the extradition of the defendants intended to discredit the research work carried out by this Prosecutorial Investigation Unit linking it to the previous administration of the records of the case by the then judge and current defendant Mr. Juan José Galeano.

It is public knowledge that these proceedings suffered serious irregularities. This Investigation Unit neither ignores nor hides these facts which, in addition, were revealed by another Argentine court, when it ruled that “… the evidence produced in the debate allowed proving a substantial violation of the rules of due process and legal defence, as the trial judge’s unfairness was demonstrated…” (Federal Oral Court in Criminal Matters No. 3, case No. 487/00, entitled: “Telleldín, Carlos Alberto y otros s/ atentado a la AMIA” [on AMIA bombings] pp. 115.126/115.128)

It is essential to specify, in this regard, that the irregularities found in the investigation were aimed at falsely attributing responsibility to Argentine nationals for participating in the attack. That is, the accused Iranian Nationals were never affected by any irregularity; on the contrary, this circumstance benefited the position of the now accused Iranian Nationals because, for a while, it diverted attention from them and focused it on a false lead.